How do you know when a spark is worthy of an inquiry? I often ask myself this question, as there are

so many sparks igniting in a curiosity-driven classroom. Some day it seems I just keep saying: "Wow, what a wonderful idea! What else would you like to do with it?" over and over. I do wonder, too, if my own passions for certain topics give more weight to ideas than others. Certainly this is the case with the return of bey blades in the afternoon. I know that I could really embrace this play, challenge the players to new ways to play, notice, and plan, and I could begin focusing my documentation on them. I am, however, ready to move on from the wonders of things that spin. When we returned from March Break, with older inquiries winding down, I was watching and listening carefully to students at play, looking for possible new directions to explore.

From the FDEL-K document section pertaining to science:

"While engaging in science and technology, groups of children may undertake

projects that involve in-depth study of a particular topic. Such projects constitute

inquiries that involve children in seeking possible answers to questions they have

formulated themselves, in collaboration with the EL–K team, or that arose during

the course of earlier investigations. These projects are based on what children are

theorizing, predicting, wondering, and thinking. Many projects evolve from, and

contribute to, socio-dramatic play. Projects should include many opportunities for

representation that permit children to return to what they know, rethink, and integrate new knowledge. Children learn best from topics they can explore deeply

and directly. Abstract topics (e.g., rainforests, penguins, planets) are difficult for

children to conceptualize. The focus for any inquiry must be drawn from what

is familiar to children in their daily lives".

The Full-Day Early Learning – Kindergarten Program (draft) pp. 112-113

|

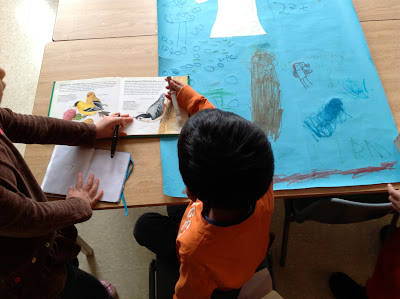

| An illustration for a story about some noisy woodpeckers making holes in trees. |

So it is that initially I wondered if I was unduly influencing my students with the ongoing inquiry in both the AM and PM classes: birds. I am an avid birdwatcher and have been since I was a little girl, when my mom first taught me to identify local birds by ear. Back in March, the wonderful Lilian Katz had sent shivers through the assembled crowd at the conference I attended, when she spoke about a boy who asked for help so that he could explain some new idea.

In the post about that conference I said: She described a child who had made a new discovery but didn't know exactly how to record what they just found out: "Show me how to write this!" he said. He, like all students immersed in deeply satisfying play,

"learned the academic skills in service of his interests".

In the months since that talk, I have thought many times about this "aha" moment when that boy discovered the power of writing to share an exciting idea. I thought about such a moment in my own childhood, one I don't remember entirely clearly but have heard told by my parents on multiple occasions. I was not yet in Kindergarten, so I may have been four years old. One morning, early enough that I was up before the rest of the family, I ran into my parents' bedroom yelling: "Mom! Mom! Come! We have redpolls!"

Well, this is remarkable for two reasons. For one, redpolls are a fairly rare visitor to feeders in South Ontario, except in very cold winter weather. I had certainly never seen this bird before. This means I not only used the Peterson bird guides (shelved with the binoculars beside the kitchen window where we could see the feeder) to identify a bird from a page filled with similar-looking birds, but I also figured out how to read the name of the bird. My mom did indeed come running, and I was right - a hungry flock of redpolls were gobbling seeds below the feeder outside our window. I was learning to read non-fiction texts "in service of my interest". That is the power of allowing student interests to dictate the content and design of daily investigations.

Birds, a love of mine my whole life, began to interest students as robins and blackbirds first appeared back in March, followed by worm-probing starlings, mallard ducks in the creek beside the school, and the majestic vultures that have flown over once or twice this spring. Looking back over old 'tweets', I identified March 28th as the day it started: "New spark today when 2 boys say they saw a "red bird" but can't decide if robin or cardinal. Dug out poster, binocs".

|

| Photo that accompanied the tweet. |

The poster I dug out for them now hangs beside the window and is consulted daily. I set up a "bird-watching window" with binoculars, field guides and a few children's books on backyard birding. We went for walks to the park, taking the long way along the river to look for ducks. Students started to record their "noticings" to share with friends at share time. My love of birds means I have the tools and toys to explore them, so when students began to report their daily bird counts or ask about what they saw, I turned to my field guide and trusty "iBird" app on the iphone. I looked up birds by request, played the songs and calls, and before I knew it, birds were all some kids could talk about.

One cold, blustery day in early April, I went for a run with my friend and Kindergarten partner at school, D. We run along the lake and sometimes slow to pick up treasures (driftwood, stones) or make a note to return with the car. D's tweet about our finds that day: "Two K teachers on a run @KinderFynes ran with a bird's skull and then we returned to get an empty nest, birch log, and tiny pine cones".

|

| Various nests collected over the years, shells left by wading birds, starling skull. |

One of my PM boys who had asked for the poster was beginning to take a leadership role in the growing inquiry. I quickly noticed his interest and expertise when he would tell me little facts: "Nuthatches go down the tree" or "Woodpeckers eat spiders and insects", which are both true. I was truly impressed by his crow call. Still, when presented with the challenge of identifying the mystery skull in the glass case, I did not expect this student to teach me something new about one of our common area birds. F used the observable details (black feathers, long pointy yellow beak) and the bird guides, and came up with the following conclusions: "It is a starling. Starlings have black bills in winter and yellow bills in summer, so it must have been summer". This is a Kindergarten senior student proving Lilian's point rather beautifully: F used non-fiction texts to gain information, and drew conclusions based on evidence. I had never made the connection between the seasons and the colour of the starlings' beak. Someday I wonder if he'll be as surprised as I am to hear the redpoll story.

J, a student in the AM class, has likewise taken a leadership role in the growing bird inquiry group. She started a collaborative interest poster with a carefully labeled diagram of a robin. Her many pictures and diagrams shared with the group lead her to come up with a wonderful idea one day: "Let's make a book about birds". When I asked if she wanted to share with families too, which is what we do when we make our online Voicethread books, she added: "How about: We Can See Birds! A book about all the birds we see". This story and many more have unfolded in the weeks since I first hung the poster and set up a bird-watching window. Bird interest centres popped up in several places around the room, and students began making their own individual bird Voicethreads. That, however, is a story for another day.