|

| The sign that greeted visitors to the Artists at the Centre 15th (and final) Annual Exhibit this spring. |

The transparent sign above is a beautiful visual metaphor for documentation: how we leave traces of our thinking matters, we must take into account the different perspectives those reading our documentation will have. It struck me at once as both subtle and powerful. The exhibit beyond the sign was a magnificent example of pedagogical listening on the part of the educators and artists in the project - each moment or time period lovingly captured and presented with the utmost respect and admiration for these capable children. There was no photography permitted at the exhibit, out of respect for those children whose works and likenesses were displayed there. I went this year, like last year, with my teaching partner and treasured friend Pooneh (who I am sad to say has since moved on to help start a new class in our school). We chatted about the projects we saw, several times finding extensions we could bring back for ongoing inquiries in our class. Mostly, however, we were just struck by the quality of the documentation, and the learning depicted. I left feeling so uplifted, so inspired by the vision of such rich learning by children from infancy through what we call "early years", I was sad to see this wonderful project come to an end. I am grateful that similar stories, overlapping the Artists at the Centre project within Mohawk College's "Together for Families" project, are shared in the book below. It presents the inherent brilliance of children as beautifully as any documentation I have seen.

| |

| My favourite book to pick up for a little lift - gorgeous documentation of capable learners at work. |

Part of my learning journey in the last few years has involved trying to balance the expectations from outside the classroom: parents, older grade teachers, principals and many others have ideas of what should be happening in a kindergarten class, though firstly and ultimately it is the Ministry of Ontario document and reporting guidelines that we need to keep in mind. On the other side of the scale, my own learning journey, my research and collaborations with other Reggio-Inspired educators, which leads me towards uplifting the students' voices and celebrating the "hundred languages" of children. Carlina Rinaldi, in the two following quotes, captures those values I've been trying to cultivate.

The school has both the right and the duty to make this culture of childhood visible to the society as a whole, in order to provoke exchange and discussion. Sharing documentation is a true act of democratic participation.

Documentation is not about what we do, but what we are searching for. ~ Carlina Rinaldi

|

| Building "body balance" challenge structures have been a part of our classroom for years now, as older students pass this idea on to their younger classmates. What fascinates me is the way the play evolves, and how I see different aspects in each photo. This picture, from this year, shows a careful placement of shoes in a special "shelf" placed there for that purpose. None of these current students were a part of the inquiry in which our class tweeted another about our body balance structures (that story from 2013-2014 in this post), thus none of them know it was an idea we got from photos we received from that other class, in which they labeled "start", "stop", and "shoes here". |

I have been thinking a great deal about documentation, both more recently at the end of the school year as I worked my way through reporting for the year-end summary of progress, and more generally over the year, as documentation became one of the dominant lenses by which I view my practice. It is something I've been fascinated with, along with the culture of a classroom around the view of the child as curious, capable and co-constructors of knowledge, since first delving deeper into my own Reggio-Inspired journey. It came to the foreground when I went to a provocative gathering of minds; documentation as relationship: BECS Conference 2015 where we were encouraged to question our understandings and beliefs about documentation and our roles as teacher-researchers. I started a series of posts about documentation, exploring my own thoughts, and also sharing those of inspiring friends who were with me on this journey, whether near or far.

When I first thought about the idea of looking at documentation as a thing unto itself, I struggled to capture the image of what it was I was trying to share, making it difficult to put into words what I was asking for when I pitched the idea to prospective featured guests. I knew I was approaching educators whose documentation highlighted student voice, a clear image of the child, a positive view of negotiating difficult topics, or simply beautiful storytelling that illustrated the brilliance of children. I am grateful for their examples and their leap of faith to join in the conversation. As I said then:

...they all managed to clearly convey in their documentation an idea that I'd been grappling with for ages. They each created work that I immediately connected with as the exemplar for the concept I'd been chatting about in ReggioPLC discussions, or reading about in various publications. Ideas that were deeply meaningful to me at this point in my journey - risky play, the view of the child as capable, inquiry as a moment or a process, documentation as shared ownership of storytelling, inquiry as a process fraught with doubt - all ideas that suddenly had a link, for me, to these inspiring educators. (from "making learning visible...", July 2015)

As I wrote that post introducing the series, it came to me ("aha!") that there wasn't an image in my mind, but a great jumble of images and sense memories.

That aha was this: pedagogical documentation is not one "thing", it is both the process and the product born out of the relationships between materials, learners, and method of documentation. The aha was that I still didn't have a big picture, though I had many pieces giving me a wider view of what I was looking at. In fact, there would never be a big picture, not an accurate one, when the ongoing process meant the view was always changing. Lastly, I realized that what made me reach out to these educators was exactly what had made me reach out to Tessa over a year ago to ask for her view of the teaching partner relationship (taken from my intro to her post):

There is something about the way we share a view of children (as infinitely capable, curious, fascinating) and teaching (as a wondrous journey, forever deepening and growing out into our lives) that creates real friends through the ether. (from "looking for the big picture", July 2015)

Last year in spring, my teaching partner Pooneh and I spent a wonderful day in the Hamilton area, first visiting the annual exhibit by "Artists at the Centre", then a relaxed afternoon sipping tea in her shady backyard in what I have come to think of as "waterfall country". We were both so inspired by the depth of learning shared in the beautiful documentation at the exhibit. We felt so uplifted by the image of the child that shone through in all of the documentation, and it helped set the intention to further study our own practice in the future.

We talked about our own class (then winding down after our first year as teaching partners in a just-transitioned full-day Kindergarten class), and our hopes and dreams for the year to come. I was already planning a trip to Boston to visit Wheelock College, where the next "Cultivate the Scientist in Every Child" conference was being held at the Hawkins Exhibit opening weekend. My love of Frances and David Hawkins's work overlaps greatly with the ideas I was seeking out in my documentation study: the child as agent in learning through collaboration with others (teachers and children alike) and with materials. I wanted to reflect this, especially the big ideas unfolding through collaborative inquiry play, and mentioned to Pooneh I was interesting in trying something I had wanted to do for a few years - a year-long growing display of documentation, chosen in negotiation with students, highlighting their favourite moments each month. She agreed, saying something like "give it a go." Like the class twitter I started a few years before, I had one idea in mind but quickly saw it change and grow as a small group of interested students took more ownership of the content and messages shared. In the photo below, the "year of learning" wall is behind Pooneh and I, filled only up to March (the April documentation was chosen, printed, and awaiting student additions such as titles or observations). The artwork on the right was hung for our guests at the Open House; we were displaying works featuring "colours of emotions" while the next months were empty. By June the entire board was filled with photos, drawings, typed conversations and student writing. After our last day of school, I took everything down and assembled it into a large book for next year's families and students (new and returning seniors) to flip through.

Families, tonight we welcome the new families and friends joining us next year at our a Welcome to K night! pic.twitter.com/TnvvjXMkiz— Beyond 4walls (@109ThornKs) May 5, 2016

My hope for the "Our Learning Over the Year" wall (title chosen by students) was to create something that would communicate shared experiences and values, but also that it would be meaningful to the children in the class, not just display for the adults. I worried, somewhat, that some voices might not get shared in this project, and it helped me remember to go and seek out those whose learning was "less visible" to me or my partner when we reviewed our notes and photos.

Both children and adults need to feel active and important — to be rewarded by their own efforts, their own intelligences, their own activity and energy. When a child feels these things are valued, they become a fountain of strength for him. He feels the joy of working with adults who value his work and this is one of the bases for learning. Loris Malaguzzi, Your Image of the Child: Where Teaching Begins

The following collage was the result of one such "close listening" moment I spent with a few students. While we encouraged larger group conversations by taking images and words overheard (anecdotals captured on clipboards) back to a group meeting to share, there were many more little moments or individual inquiries that told the learning story of certain students. These stories that students weren't always interested in sharing with their class, often they were happy to share on our class twitter, knowing they would be able to show their families at home.

During play&learn big blocks are available, but even during quiet play after lunch, many materials invite building. pic.twitter.com/29vWAeNfGu— Beyond 4walls (@109ThornKs) February 18, 2016

In thinking about the "Our Learning..." wall as it grew, as I spoke to children at meetings and during play, I was influenced by my hope of hearing and amplifying all the voices within our large, diverse classroom. Two quotes helped ground me in this effort; shared below.

Children are competent, capable of complex thinking, curious, and rich in potential. They grow up in families with diverse social, cultural, and linguistic perspectives. Every child should feel that he or she belongs, is a valuable contributor to his or her surroundings, and deserves the opportunity to succeed. When we recognize children as capable and curious, we are more likely to deliver programs and services that value and build on their strengths and abilities. p.6, How Does Learning Happen?

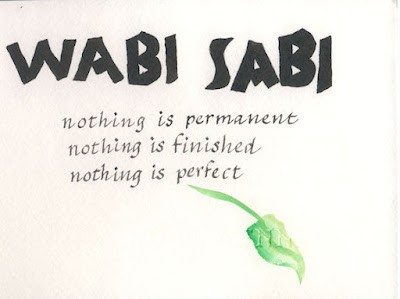

Putting classroom to bed 4 summer, tackled the desk we shared. Found this lovely reminder about what really matters. pic.twitter.com/PAyxHCLYw3— kids connect (@KinderFynes) June 30, 2015

In creating the documentation wall, I worried often if it was really "theirs". I had hoped that, like the class twitter I created but quickly found others interested in using to send messages, that this space would be meaningful to students. I didn't see much ownership, originally. I would come to meeting at the end of the month (or beginning, if a weekend intervened) and ask students if they had any ideas to share about their last month together. If few ideas came up, I would scroll back through photos and share a few on the screen, prompting conversations. Some students wanted to draw or write their stories, but I wondered if there would be enough to capture some of the bigger moments: the aha's, the break-throughs, and so I'd carefully select images to show to see if those would spark connections to other ideas shared. I had hoped to tie together big threads when I suspected a project might emerge, but I was reluctant to do so if it wasn't coming from the students first. So I armed myself with questions, photos, and my notes, and asked each month what we might share on our learning wall.

Over the year I noticed changes; some months had many drawings, other months none. Some projects faded away one month (though it continued in class) and came back into view in later months. I wondered many times if it was truly meaningful to our students, beyond the point at which we co-created it. Was it just a display for visitors? Was it alive when being created, then dying on the wall?

Then I witnessed several moments when students interacted with the documentation on the walls (as opposed to the much more popular project books or our twitter), and I realized I had to see the project through to the end of the year. I saw students seek out images of other students who'd moved away over the year (in our class we lost and gained many students this year, more than usual even for our high-transition neighbourhood). I witnessed new students ask their classmates about documentation they weren't present for. A particularly moving incident occurred when one of our new students from Syria hopped up on the counter to point out students in the photos. She had been a watchful participant for a few months, very happy to participate and demonstrate her understanding through gesture, drawing, facial expressions and few words. This day she confidently pointed and named everyone she recognized, and asked the other girl to name those students who were no longer in our class.

EA is showing RL all the peers she recognizes. They were reading our year of learning wall together. #documentation pic.twitter.com/m0cOp6rqdd— Beyond 4walls (@109ThornKs) April 22, 2016

A moment which shows learning happening during play&learn: AK took over documenting when both teachers had full hands pic.twitter.com/I8oT6S7jut— Beyond 4walls (@109ThornKs) March 2, 2016

Sometimes there are math explorations happening right under our noses, but we have 2 ask to understand! #playmatters pic.twitter.com/cazU53TfZi— Beyond 4walls (@109ThornKs) April 22, 2016

We made a stage and try to balance, it's a kind of yoga pic.twitter.com/BgnD6J9zxN— Beyond 4walls (@109ThornKs) June 9, 2016

These examples I shared are ones I feel proud of, moments that I can look to and see evidence of our message about children's learning to families and other adults who view the documentation. (the last tweet was captured and shared by Pooneh; note the students with clipboards, one with the plans used to create the structure, the other documenting the participants in action).

I was struck by a thought that occurred to me as I took in all the stories at the Making Thinking Visible exhibit: "The power of being seen and heard - our documentation carries weight". I wondered about our class, about students who felt heard and seen, and those who might not. I struggle to find ways to capture and share the moments of breakthrough in students whose starting place was very different from the majority of their peers - those students for whom spoken language (English or other) is not part of their expression, for whom we must listen and watch much more carefully in order to understand them and take their needs and wants into account.

Documentation can serve to illuminate the thinking, a change in thinking that occurred, what was learned or not learned, the evolution of the behaviour questioning, maturity, responses, and opinions." - Wurm, 2005

Over the year as I reflected on the documentation we shared on our learning journey wall, as well as the copious notes and photos I used for more individual assessment and planning, I felt at some moments that I wasn't measuring up to the goals I had set myself. I was cognizant of differences in attention and relationship, and though it is natural that in a room with two main educators that students would gravitate more towards one or the other, I still sought out those students we might be missing. It wasn't an easy task in a year with such changes - six students moved in after January, and none of those had been to school in Canada before our class. We were always forging new relationships, following new inquiries, capturing clarity and confusion in our large and busy class. I looked to others who were also struggling with these aspects of documentation, reading blogs and articles and participating in #ReggioPLC chats.

I appreciated "The Dangers of Documentation: Ensuring Equity in Your Work"for Joel Seaman's thoughtful look into how students might get overlooked in the larger sharing of documentation with the learning community including families. I especially appreciated his caution not to feel implicated, because this work is difficult and new, and we are all learning as we try to create our new habits of mind around this important part of our role in the classroom. Reflecting upon one's practice is at times painful though it is entirely necessary.

We need to be advocates for the plethora of authentic learning moments that occur, even while others may just see "play". Without documentation, these brilliant moments pass by and are completely lost.

As you look over your documentation, ask yourself - "What is being documented?" "Who is being documented?", and "Why is this being documented?". (Joel, The Dangers of Documentation...")

It was difficult to read and not immediately think about those whose stories were told quietly (to family only) or privately (in small group) for respect for privacy, or fear of being misunderstood (when the growth was enormous but not easy to share with respect to dignity, such as a success in toileting or a newly mastered form of expression). I loved the post and yet felt uneasy, always wanting every child in our class felt honoured, heard, and loved, and not always knowing how to do so with shared documentation. It is a conversation I hope to keep going, as I learn more about teaching and learning along with students with special rights.

This post by Allie Pasquier stopped me in my tracks when I read it, though, and I realized how being hard on myself wasn't a way forward. I so appreciate her honesty.

Are we giving ourselves enough time to understand what is happening in a group or in our center? How do we get under the surface more often?

Working with children is a creative process, and it takes an incredible amount of time and energy - much more than we are paid for. The reward is in the moments when you solve a problem, when you feel you have grasped an idea, when you have stories to share with children, colleagues, families, and the community about the work that is happening in your space. There is no exact formula for early childhood education, and I hope we never find one. As educators, we can’t be perfectionists. Every child is different, every group of children, every school, every community. As professionals, all we can do is practice, reflect, and practice again. Let’s try to fight those feelings of inadequacy that we all have by doing something to make our teaching practice our own - not someone else's. (Allie Pasquier, "It's not about the branch")

|

| Outside the Artists at the Centre exhibit and where our last group meeting was held. |

Perhaps the biggest part of my learning journey, not in terms of time but indeed in terms of the impact it has on my thinking, is the Documentation Study Group meetings: "(A) group of educators and artists in Hamilton has made a commitment to meet monthly for in-depth discussion of the Reggio philosophy, and collaborative reflection on documentation." Our final meeting of the school year took place beside the "Making Thinking Visible" exhibit. We all had an opportunity to wander and take in the documentation before we sat down to share ideas. As mentioned earlier, there was no photography permitted of the work, however there was a handout provided to visitors explaining the project.

This is not an art exhibit. These works are significant because they show us images of what the children are thinking and how they are making sense of the world. They show us how adults and children can think and learn together. The show us that non-verbal languages reveal thoughts and feelings that, once expressed, provoke further thought and expression. They also challenge us to reconsider our view of children's capabilities. We see evidence every day that children are born ready to enter into relationship, engage in interaction, form theories, explore and learn from everything the environment and their imagination brings to them, and to do it all joyfully.

Documentation helps us see the intent and process as well as the impact of adults and children collaborating. It gives visibility to our learning, and offers others theories for consideration. ~Karen Callaghan, Project Co-ordinator, in the "Making Thinking Visible" handout shared at the exhibit.This passage helps illustrate the importance of sharing our work, but also of getting it right. An idea we discussed that evening was that it is an intensely personal thing we do, putting kids' work in public to be viewed and critiqued. We didn't all agree on the best way to do so (some of us much less comfortable sharing identifying features and names of children, others of us seeing it as the way to honour the children best) but it was a wonderful conversation in which we all agreed we would want every child to be able to look back upon their work (as the children visiting the exhibit had done early that month) and feel pride. We referenced the Hamilton’s Renewed Charter of Rights of Children and Youth, which we had delved into more deeply at an early meeting. I recall I burst into tears, thinking about how powerfully we can harm a child or lift them up, with what we share when making the learning visible. It is a sacred trust we have, taking children into the world and opening their ideas and works to potential misunderstanding. Yes, our duty is to the school, the reporting deadlines and the Kindergarten Program that outlines our program expectations for learners and teachers alike, but while documentation with an assessment lens can highlight the gaps and mistakes in learning, that shared with our larger community ought to take into account a relationship lens.

One particular educator, Tracey Speedie, spoke of this eloquently at our meeting. I think it was her (my notes continued onto another page) who talked about thinking of a student in terms of "his position as a citizen in your class", one with rights and responsibilities and thus our role in ensuring those rights are met and not trampled on is tantamount. She kindly agreed to let me share her words here (paraphrased as I wrote quickly but may have missed a word or two!)

The notion I'm worried about is privacy, and respect. The children are sharing with us who they are - there is no guile, no filter, but their interactions in the moment. They are absolutely authentic with us, when working with materials, when figuring out what's right and what's wrong.My own thinking from this conversation, scrawled in the notebook I lug everywhere, is around the the power of documentation to link students over time, and also the importance (and difficulty) of representing students whose language is not ours (whether spoken or not).

We are right there, seeing a true picture of these children, warts and all. If we document with an assessment lens, as opposed to showing their brilliance... we are breaking their trust. (Tracey Speedie)

A pedagogy of place - students who have siblings at school, who were in our class before them, they know the stories of the land, they connect to the images and stories we keep in our project books.

For younger students or those not yet using English to communicate, it is upon us to do the work to find the common language in their actions - read them, communicate, amplify their voice as we can.

Next year brings a brand new teaching team (both ECE teaching partner and ERF working with us to support student needs where special rights exist) and a newly-published Kindergarten Document. I look forward to exploring further, through the summer with multiple inspiring visits to the Wonder of Learning exhibit, and in the new school year as our class comes together. I also look forward to reading the new Kindergarten Program, because the glimpses I've had thus far have shown our ministry to be continuing a journey in early years that intertwines with my studies - a view of children as learners that demands we meet their unique needs and skills and allow them to participate in the way they are comfortable.

The new document invites us not just to do some things differently but also to think differently and listen differently. We recognize that it would be unwise to push for quick adoption of new practices. It should take time for understanding to be constructed at a deep level. Quick change in practice would suggest superficial understanding of why and how all the aspects are interrelated. ~ Karyn Callaghan, in Inspired and Inspiring Change in Early Childhood Education in Ontario

I know I have wandered today as I wrote, revisiting many days over the year that have informed my understanding. I leave with some examples of from our class, of learning from and with documentation:

|

| More collaboration in the big building area to create a balance challenge - inspired by our newest #discoverybin. Click to see great examples of listening our bodies (balance, stable) to materials, and to each other. |

The following three examples are vine clips, as such I left them as links rather than embed here (which can in some formats result in noisy autoplay). Simply click through to see the links.

These 2 students are carefully listening to their bodies & the blocks to build a stable, safe structure.

KU & ZA saw a ball run from last year (w/ KU in pic) and revised their design accordingly

LA started today. She asked when we go home. ME is reading in Arabic for her, showing what's now, what's next...

Examples of documentation with and about students engaged in play - these glimpses remind me of times when students were deeply invested in telling their stories and sharing them with others.

— Beyond 4walls (@109ThornKs) April 5, 2016Yesterday we had a very fast, fascinating visitor in our class. It inspired us to do research & draw our observ'ns pic.twitter.com/ACg6n9kmsZ— Beyond 4walls (@109ThornKs) April 5, 2016

Our centipede guest came back up the pipes to our sink today! It's become a regular guest. @zikmanistobin pic.twitter.com/Db2vcdXtB9— Beyond 4walls (@109ThornKs) April 6, 2016

Our seeds are growing nicely, but our vegetables are also still showing signs of change! #gardeninquiry pic.twitter.com/aaPsn3TCiG— Beyond 4walls (@109ThornKs) April 15, 2016

Measurement can happen anywhere in Kindergarten - here's a fun way to compare height. pic.twitter.com/paAa40Qgka— Beyond 4walls (@109ThornKs) April 12, 2016

I hope to feature more guests in this series of posts about documentation. If you have questions, comments, or would like to add your voice to the discussion, please let me know with a comment below.