| |

| My daughter and other children climbing on the "best part of the park" after hours of walking through the spectacularly beautiful Stanley Park in Vancouver, BC. There are beaches, swimming pools and splash pads, winding mountain trails leading to breathtaking views of the ocean. The park is filled with play structures, a fantastic aquarium, and the beaches with waves. This downed tree, however, an artifact of a terrible storm that took down several "grandfather trees", was her favourite when we last visited two years ago. It took a few minutes to capture a photo without a crowd of kids, all ages, hanging from all the branches or scooting along the trunk. Here's another view, complete with crowd. |

It is a hot, indeed steamy day today as I sit to write. I spent part of the afternoon out on my bike with my daughter, riding up the local ravine through which the Etobicoke Creek flows, sometimes slowly, but today noisily after last night's wild thunderstorm. Everywhere we looked there were signs of the violence of the storm: deep brown, churning water flecked with white foam, downed boughs clogging the creek where it widens down by the lake, smashed flowers and leaves on the footpath, leafy boughs and refuse caught in branches hanging over the creek, evidence of the higher water level carrying flotsam and jetsam high above the banks. We paused awhile in the forest, up past the cascade that today rushed loudly like a waterfall, around the bend where the trees arch over and it feels like the city is far, far away. The rain was long gone, now, and a hazy sunshine beat down through humid air, but when the wind blew it dislodged droplets from the leaves overhead and it rained anew as we took refuge in the shady forest path.

|

| The creek, usually clear, looked brown and frothy after last night's storm. Look closely at the water's edge right above the straw bale (another gift from the storm? It appeared since my last visit days ago) to see the night heron fishing in the cascade. All over this spot, one sees evidence of storms past: cracks in the pavement above, whole sections broken off and washed downstream, chunks snapped and resting precariously like the one on which the straw bale rests. It is a reminder of the power of water, and fragility of structures that seem unbreakable. The cascade is a favourite resting spot for birds and people alike. Click here to see the heron lift off and fly away, after catching a fish. |

I am always struck by the beauty of the ravine, though it is not landscaped or kept clean like the beautiful Marie Curtis Park at its very southern end. It is a wild place, but there is evidence of people all around, too: broken glass, plastic bags caught in trees, shopping carts barely visible below the water's surface in the shallows below the first cliff. One hears planes fly overhead, trucks rumble by on nearby roads, distant dogs barking, and occasionally music drifts down from homes high above on the eastern edge of the valley as we ride along the trail.

There is something rather remarkable about an urban ravine, a place that is both wild and also entirely constrained. Back at home, nearby, the city trucks come by and remove the dangerous, the ugly, the roadkill, the garbage. Here in the valley we see it all, and watch it change and sometimes become something beautiful. Downed trees become a bridge to climb on, broken concrete a new challenge to explore. A bloated carcass of a raccoon loses its hair, then its shape, and much later, appears as scattered bones and teeth, often with traces of gnawing or scraping by scavengers.

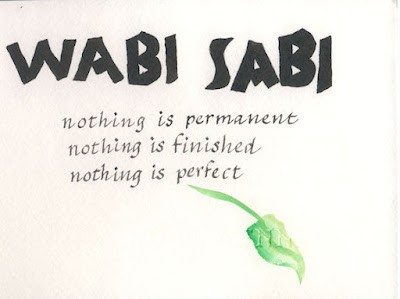

Our ride today wasn't a long one, as the heat was oppressive and the water too busy to stop and soak our feet at the cascade. I thought of how Cooksville Creek beside our school might look, as it is also prone to flooding after a storm. I wondered if the no-mow zone was again littered with debris from the high water, or if any students were watching the creek gush past under their feet from the bridge beside our school's driveway. Thinking about our tiny, concrete-bounded stream which gurgles past the yard with litter and wildlife alike, I thought of how lucky I was to teach at a school with something wild right beside it. Not perfectly wild, to be sure, but living water nonetheless. It made me think of an idea I'd tucked away last year, a blog post I had started by saving a storify conversation. I've long been attracted by the idea of "wabi sabi" but at the time was beginning to see how it was a part of my teaching practice. So it was last year I left myself the fragment in blue below, along with the photo of the beach glass and ceramics I'd gathered that day. I remember it struck me, as I picked up and turned over each piece I found on that sandy, stony beach, that this favourite pastime of mine was a metaphor for learning and growing, the way one turns over ideas, tosses back those that no longer make sense (and on the beach, that I always toss back the rough, too sharp pieces which need more time in the waves) and makes room for new ideas. Left in draft so long ago, now when I came to revisit I know I've forgetten many of the ideas that circulated when I left these traces. New events touched on old ideas and they became changed, grew a part of how I understood the challenges I faced over the year: saying goodbye to our beloved cat after fourteen years; seeing our class grow, shrink, and grow again as students moved away and others took their place; welcoming students whose families had fled Syria and learning so much about resilience as we played together, grieving for my uncle who passed this year but learning to appreciate him so much more as I listened to his stories from friends and family at his memorial; losing my teaching partner at the end of this year as she moved on to help open a new class. Naturally I look at the handful of glass now and see with different eyes. But my understanding of what is beautiful, what is worthwhile sharing with students and families, and what is worth celebrating... that only grows. My understanding of what matters, and how learning happens, has grown tremendously.

the convo that led to a new understanding...

| ||

| Finding

beauty at the beach - pondering the beautiful colours and mysterious

origins of the treasures I found this week at the water's edge.

I know the beach glass represented, as it does for me still, the beauty

of something transformed by relationship - broken, discarded, and yet

made precious by its time tumbling in sand, stone and waves. I have

collected treasures such as this on my local shore for many years now,

for loose parts creative play and for giving away. Those pieces, each a

shard of something that was whole, now a part of a collection, represent belonging.

Now I am aware that all this preamble might seem completely unrelated to teaching and learning, the stated theme of my blog. It is, however, entirely related to how I see learning and growing. As a child I was concerned with "getting things right" at school, that is to say, following instructions and getting good grades. I wasn't a success socially, not during elementary school, but academically I fit right in and it made me feel safe (recess was another matter entirely). I had glimpses of a bigger world, through travel to France and Spain as a teen. I experienced "otherness" and the feeling of not belonging, not being able to express myself in my new surroundings with my limited language, thinking teachers must think me dumb. But the stakes were low: my marks at home were fine and my time in Spain wasn't going to count against me. It wasn't until later, in university, that I discovered my ability to fail. I found it terrifying at the time, but not understanding what was expected was a gift, one that allowed me to begin to look critically at what mattered. Studying post-structuralist thought made me panic, as though the cognitive dissonance I felt was actual walls coming down around me, and not merely old ideas crumbling. I found that I couldn't look at anything the same way once my eyes had been opened to the world, my small-town view bust wide by my big city surroundings and multi-cultural friends. Most painful was a new way of looking at "whiteness", from the myriad points of view as I made friends from various continents including aboriginal Canadians. Seeing racism directed at friends made me fiercely protective and yet terribly hopeless. I didn't want to be a part of it, but didn't know where I fit. My own family home was a safe haven, a place of guests and stories and generosity and fun. But when I looked at myself with this new lens, of not-white, I couldn't see beauty anymore. I felt broken. It took time to find the beauty in that break.

Safe to say what I experienced is not uncommon for any small-town kid who goes too far from home and doesn't know where "up" is. It took time for me to connect to what matters most to me, what I missed most about home - nature. I learned to see the life heaving in every corner of the city, not just in the big parks or along the shore. I learned that I remain passionate about equity and it has a place in my teaching practice. I learned that breaking isn't a bad thing, if it means letting the light in. Learning involves letting go, and assimilating, and growing. For that reason, I connect deeply with the idea of wabi sabi, as I understand it. A few years ago I found a beautiful book written for children, touching on the meaning of wabi sabi. I was so delighted, I immediately bought more copies, knowing it was a concept I shared with others in my Reggio-inspired PLN. It resonated with me as deeply as the poem, the 100 languages. It struck me that embracing a wabi sabi view of learning was the only way to ensure all voices could be heard, all those 100 languages and 100 more. Being appreciative, rather than fearful, of things unexpected... leads to wonderful collaborations through playful inquiry. Being brave, that is, unafraid to make mistakes and face the consequences - that was not possible in a "lessons first, play as reward" classroom as I first saw and practiced when I began teaching back in 2003. Seeing diversity as much more than culture, language or colour, but encompassing ways of being beyond what is "neurotypical" - allows me to understand my own thinking better as I learn to understand that of others. Not having a set idea of how our classroom "should look" helps too, though I am often struck with self-doubt upon entering rooms of peers who manage to make their space showroom-perfect. Negotiating our space with students, talking about how we use our materials and our furniture and our bulletin boards - curriculum emerges as does the look of the space we share. Back in the spring I tackled this idea as well, this question I have about the meaning of beauty and how (or if) is it meaningful to teaching and learning. In describing it as one part of a "tangle of spaghetti" I was attempting to unravel, I said: One such "noodle" running through my mind was the idea of beauty: What is beauty? What does it mean to enjoy something beautiful? Is beauty important to play? Is beauty important to learning? Are there shared ideas of beauty across the diversity of human cultures and across age groups? Do our notions of beauty change as we grow and learn? I continue to ponder this idea, but without a perfect description of what it is, I still think seeing beauty in what might otherwise seem mundane leads one to see possibilities everywhere. Seeing beauty in others, especially when they are unable to see it themselves, is one of the greatest gifts we can give to a child or adult.

|

* * * * *

As I think of my relationships with students, teaching partners, and the larger community that come together around our Kindergarten class, I am struck by how much reflection goes on as we examine our world together. We find meaning through our interactions, and through remaining open to a world of natural beauty, we learn so much more than is possible in an organized, sanitized version of teaching in which only the proper, good, clean, pre-made materials are considered for use.

|

| A favourite page from "Wabi Sabi". |

As I think of my relationships with students, teaching partners, and the larger community that come together around our Kindergarten class, I am struck by how much reflection goes on as we examine our world together. We find meaning through our interactions, and through remaining open to a world of natural beauty, we learn so much more than is possible in an organized, sanitized version of teaching in which only the proper, good, clean, pre-made materials are considered for use.

“We do not learn from experience... we learn from reflecting on experience.” John Dewey

|

| Several days' worth of dandelions, lovingly collected by students during the first few weeks the flowers emerged. Treasures from nature always wind up on the "look closely" table under the window. |

| ||||

Dandelions, like fall leaves, become a part of play and exploration for weeks. They decorated "sand cakes", became necklaces and crown, were rubbed onto drawings to impart their golden glow, added to the snail globe to "give the snails something nice to eat and smell", places in vases, dried and ground up in the mortar and pestles, added to potions.

|